Back to - Commissions

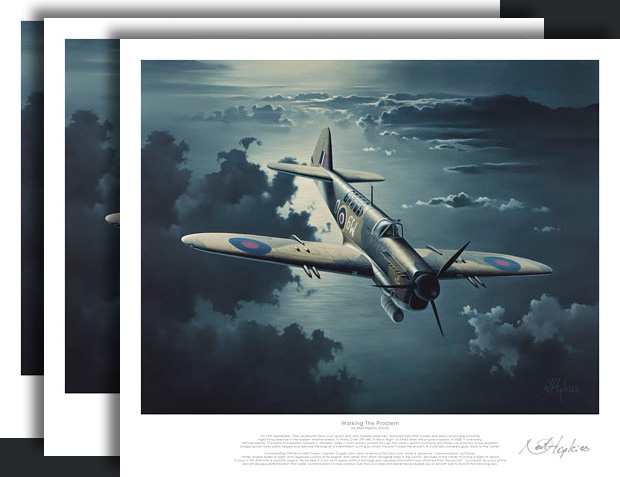

WORKING THE PROBLEM

Oil on Canvas 30" x 23"

This was an interesting commission depicting a true life incident of airmanship. I was commissioned to paint the scene by the son of the pilot, who provided me with a detailed account of events and of the aircraft. After an initial discussion it was agreed that the painting would portray the moment the drama unfolded as the aircrafts engine stopped while flying over open sea. The aircraft is shown in a slight nose down attitude and losing altitude while the pilot, Harry Hunt, works through the various options that may have caused the problem. The exact cloud conditions of the evening are unknown so a backdrop was composed that would add some scale and perspective to the scene. The full story of events is below.

An exclusive limited edition print run was produced as part of the commission, for distribution by the customer.

Story Behind The Painting

On 19th September 1946 Lieutenants Harry Hunt (pilot) and John Keddie (observer) launched from HMS Ocean to conduct a routine night flying exercise in the eastern Mediterranean, in Firefly O-6W (PP 549) of Black Flight, 814 NAS.

After half an hours flight, while at 6000 feet over open sea, the engine stopped. Losing altitude rapidly, Lt Keddie immediately radioed a ‘Mayday’ while Lt Hunt quickly worked through the various possible causes, surmising that there was probably a fuel contamination problem. The following is an extract from a report written by Harry Hunt describing the events that followed:

`It really is amazing how a positive conclusion can steady one’s nerves – I felt rather superior having reached my conclusions but this euphoria did not last. “We are down to 4000 feet, any luck?” This was John. I told him about my reasoning and that I intended to work on the fuel system. “Well make it bloody quick, old boy, or we are shark bait! Incidentally, we have about 25 minutes before we can expect to pick up Mother on the scope.” Was Johns reply. I needed NO further encouragement!

I was flying on main tank which I turned to off before switching off both magnetos and opening the throttle up to the gate. I left this set up for about 15 seconds and then operated the priming pump three or four times. I then closed the throttle to the idling position, turned on the main fuel cock, crossed my fingers and switched on one magneto. The engine coughed, caught and coughed again before bursting into life. I switched on the second magneto and gingerly opened the throttle. All seemed well – my fingers were still crossed!

….I asked John how we were doing – “about 15 minutes to go but we are almost down to 3000ft – can’t you get any more out of her?” to which “her” replied by coughing and again giving up the ghost. I continued my adopted routine – with diminishing success!

The altimeter was now moving far too fast for comfort – 2500ft and falling – and no matter how much I tried, the engine refused to run for long on the main tank. One action was left. There were approximately twenty gallons in each of the wing tanks. I cleared the engine again, switched to wing tanks and with “everything” crossed I managed to get the Griffon running again. We were down to 900 feet!

I set the controls for what amounted to a very long powered glide, zero boost and no more than 1800 rpm which I estimated would keep us airborne – engine permitting – for at least half an hour. The engine coughed a couple of times but continued to run – we were down to 500 feet when John picked up Ocean at about 5 miles and some 5 degrees to port. I altered course very carefully feeling that any harsh movement might disturb our present equilibrium and within a couple of minutes I spotted the ship glowing like Piccadilly Circus on Christmas Eve.

A slight cough from the Griffon reminded us that we still had to get aboard. We were now down below circuit height and I had no intention of carrying out normal procedures. Having identified the stern, I charged in. The DLCO was in his position, and without further ado, between us we completed a reasonable arrival. The Firefly was in one piece!

’ The commanding Officer of HMS Ocean, Captain Caspar John, later to serve as First Sea Lord, wrote a ‘green ink’ commendation in the log book as follows: “When engine failed at night, pilot regained control of his engine, and rather than ditch alongside ships in the vicinity, returned to the carrier involving a flight of almost ½ hour in the dark with a doubtful engine. He landed in a low wind speed without damage and valuable information was obtained from the aircraft.”

The successful recovery of the aircraft allowed inspection and the determination that water contamination of the ships aviation fuel had occurred, which prevented the probable loss of aircraft due to launch the following day.

Lieutenants Harry Hunt (pilot) and John Keddie (observer) in another Firefly from HMS Ocean, O-5W